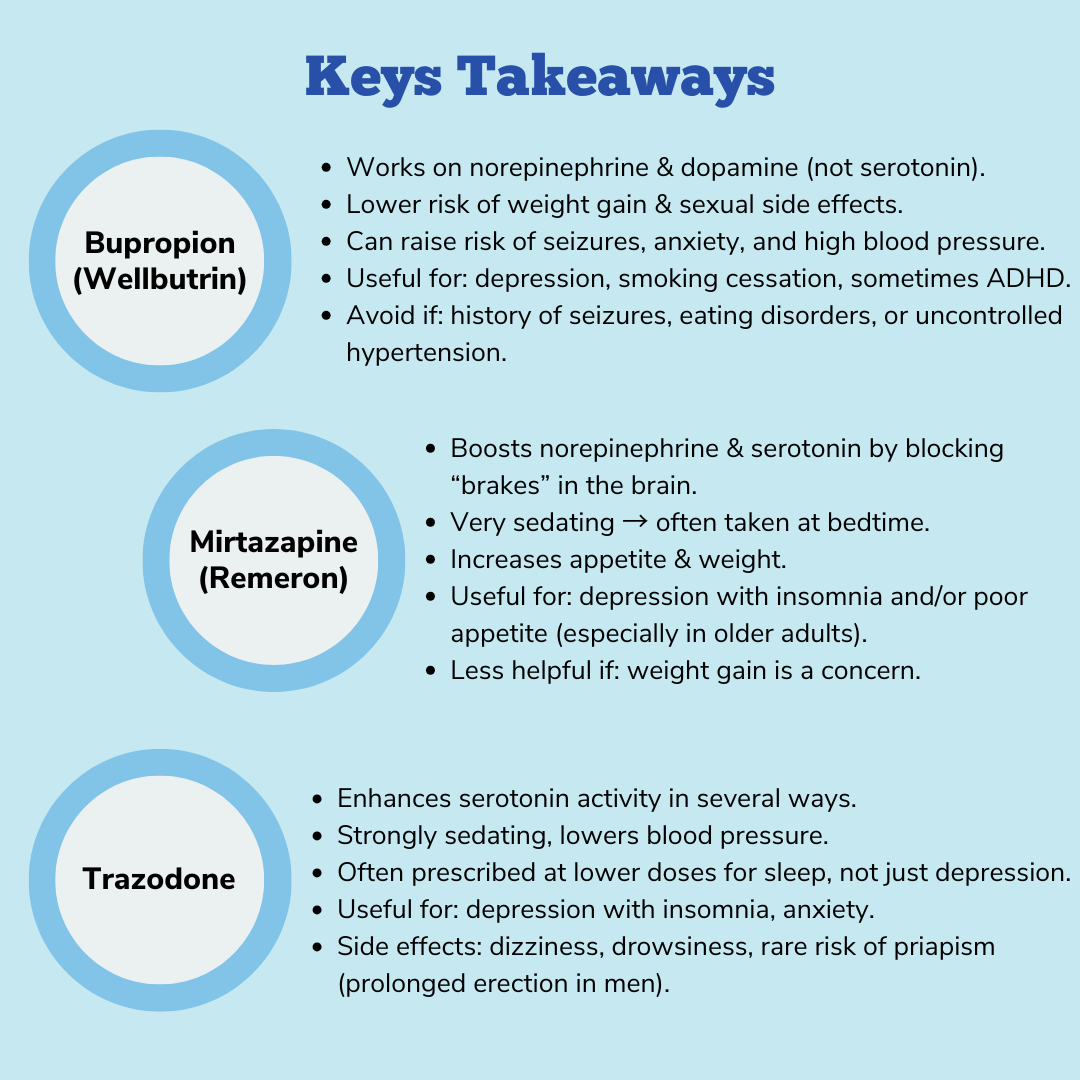

Today, we will be discussing a collection of “antidepressants” that are typically considered after trying the “first-line” SSRIs and SNRIs (often referred to as “second-” or “third-line” options) and/or in specific situations. This list is by no means exhaustive and there are myriad more options, however I chose to highlight three that are the most commonly used, and we will touch on newer options in the coming blogs. Each of these medications have a unique mechanism of action and therefore unique (if overlapping) side effect profiles, specific situations when we may consider their use, as well as additional/alternative indications, and we will touch on these differences in each section. Without further ado, here are the “atypical” antidepressants!

Bupropion:

Bupropion (trade name Wellbutrin) is considered a norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor, which means it works through (relatively weak) inhibition of neuronal reuptake of norepinephrine and dopamine. By blocking the receptors that mediate/are responsible for “cleaning up” norepinephrine and dopamine from the synaptic cleft (much the way SSRIs and SNRIs do for serotonin and serotonin/norepinephrine), it leads to changes and increases in norepinephrine and dopamine transmission in the relevant areas of the brain. Additionally, bupropion also antagonizes/blocks nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), which is thought to reduce the reinforcing effects of nicotine and contribute to its use in treating tobacco dependence.

While analogous in mechanism to the SSRIs and SNRIs, you will note that it does not inhibit the reuptake of serotonin which begs the question, how does it still treat depression? As you’ll recall, the monoamine theory of depression includes dysfunctional norepinephrine and (to a lesser extent) dopamine transmission, and recent studies have also shown bupropion also modulates a specific type of serotonin receptor (5-HT3AR), which may also contribute to its unique clinical profile.

As for side effects, bupropion has a lower risk of sexual dysfunction and weight gain compared to serotonergic antidepressants (SNRIs, SSRIs), but also carries a higher risk for lowering seizure threshold, anxiety, anorexia, and increased blood pressure. Of note, many of bupropion’s side effects are dose-related, meaning the higher rates of side effects are observed at 400 mg/day compared to 300 mg/day. Lastly, bupropion also carries the same black box warning regarding the risk of increased suicidal thoughts in individuals under 25years, as well as the rare risk of the induction of mania/hypomania (primarily in individuals with significant risk factors for bipolar disorder).

Bupropion is still considered “second line” for depression and anxiety as the magnitude of its effectiveness for both in adults is less than that of the SSRIs and SNRIs. Additionally, its effectiveness in children and adolescents has not been consistently shown/observed in studies. As noted, bupropion has shown effectiveness to help with smoking cessation (due to its nAChR activity). Lastly, there is some evidence that bupropion can be helpful for ADHD, as it works on both norepinephrine and dopamine (like other ADHD medications), however the effects are quite modest and not nearly to the level of stimulants or the non-stimulants we’ve discussed.

Mirtazapine:

Mirtazapine (trade name Remeron) works primarily by antagonizing or “blocking” presynaptic alpha-2 adrenergic inhibitory autoreceptors and heteroreceptors. These are actually the same receptors that the “alpha agonists” guanfacine and clonidine act on, however instead of activating these receptors, mirtazapine blocks or “deactivates” these same receptors. It is postulated that when mirtazapine blocks alpha2 receptors this leads (over time) to an increase in norepinephrine and serotonin neurotransmission. Additionally, mirtazapine is a strong antagonist at specific serotonin receptors (5-HT2 and 5-HT3) which blocks these receptors and channels serotonin signaling through a different serotonin receptor (5-HT1) which is thought to mediate antidepressant effects while minimizing the other typical serotonergic side effects seen with SSRIs and SNRIs such as sexual dysfunction and gastrointestinal symptoms. Lastly, mirtazapine exerts strong anti-histamine activity antagonist of histamine H₁ receptors, which contributes to its sedating effects and propensity to increase appetite.

As with bupropion, mirtazapine’s effectiveness for treating depression and anxiety in adults is less consistent/convincing than the SSRIs and SNRIs. However, given its unique profile, mirtazapine will often be used when patients (commonly older patients) who are suffering from insomnia and anorexia (decreased appetite) in the context of depression.

Trazodone:

While trazodone’s mechanism of action is not fully understood, its effects are believed to be related to increases/enhancement of serotonin transmission in the central nervous system via a complex combination of mechanisms. Firstly, trazodone acts similarly to an SSRI via (less intense) inhibition of the SERT (serotonin reuptake transporter), as well as an antagonist at a myriad of other serotonin receptors (5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, 5-HT2C). The antagonism or blocking of these receptors is considered a key to its antidepressant and anti-anxiety effects, and it also helps to minimize serotonin overstimulation that can occur with SSRIs, thereby reducing side effects such as insomnia and sexual dysfunction. Trazodone is also a partial agonist at 5-HT1A receptors (meaning it binds and only partially “activates” the receptor) which is thought to underlie some of trazodone’s unique clinical effects, including its propensity for sedation and anti-anxiety effects. The reality is we still do not fully understand the net effect of all of these various actions on serotonergic transmission and their role in trazodone’s antidepressant effect.

In addition to serotonin-based activity, trazodone is similar to mirtazapine in that is also acts as an antagonist at alpha-adrenergic receptors (α1A, α2C) and has anti-histamine activity (H1-histaminergic antagonism). Therefore, trazodone shares mirtazapine’s propensity for sedation and lowering blood pressure.

As with bupropion and mirtazapine, trazodone’s effectiveness for treating depression and anxiety in adults is less consistent/convincing that the SSRIs and SNRIs, but given its unique profile, it will often be used when patients are suffering from insomnia in the context of depression.

Conclusion:

These three medications are typically considered after trying an SSRI and/or SNRI, as they have not been shown to be as effective. However, these medications can be quite useful when a patient has not responded to the “first line” agents, as well as in specific situations (ex. mirtazapine for depression with severe insomnia, anorexia) and for additional/other indications (ex. Bupropion for smoking cessation). As always, I’ll end the blog by reiterating to please always discuss risks and benefits directly with your mental health clinician before making any decisions so they can help guide you in figuring out what is best for you or your loved one.